"Onosato Toshinobu in 1955: The Lead Up to Twelve Circles"

| by Shogo Otani (Chief Curator, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo) |

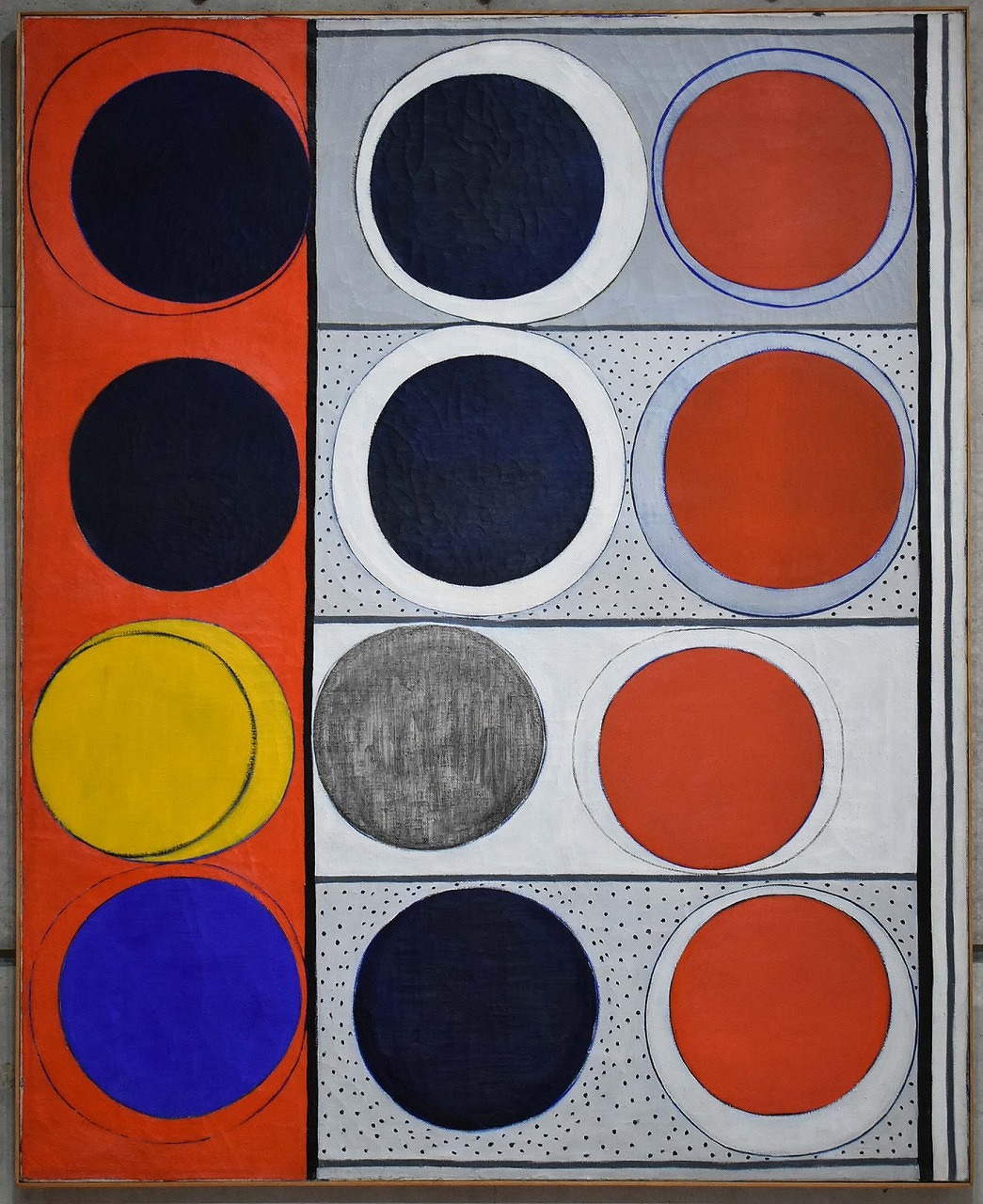

"Twelve Circles"

1955

Oil on canvas

162.0~130.3 cmiF100)

Signed, titled, and dated on the back

Exhibition History: 19th Jiyu Bijutsuka Kyokai (Free Artists Association) in 1955

Included in: gWriterfs Record - My eCirclef - Reciprocal Movement from Concrete to Abstracth in gArt Journal Vol.18,h p.15, published in March 1961.

Twelve Circles was shown for the first time at the 19th Jiyu Bijutsu Art Association Exhibition, which ran from October 9th through 26th, 1955, at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum. The work marks a turning point in Onosatofs artistic practice. Indeed, we could say that his creation of works of art consisting entirely of circles begins roughly at this point.

Of course, this is not to say that circles had not appeared in Onosatofs work before this. We see the circle as a motif within his pre-war works, such as Severed Circle (1937); Vermilion and Yellow Circles (1939–49, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo); Single Vermilion Circle (1939–40); and Circles in Black and White (1940, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; Figure 1). Yet the war forced a hiatus in Onosatofs practice. When he finally returned home in 1948, after his internment overseas, he went back to figurative painting, retracing the route from the figurative through to abstraction. The next few years were a time of working things out. As part of his gradual shift toward abstraction, circles begin to appear as an element of his canvases; in a solo exhibition in the spring of 1955 (May 9–14 at the Mimatsu Gallery, Tokyo), they seemed to occupy more of a presence within his work. Yet it was only with Twelve Circles that the circle became the sole constituent element. This transformation was a sudden one. At around the same period as this solo show, Onosato exhibited his works Appearance (1954; Fig 2) and Rhinoceros Beetle (1955; Fig 3) at the Abstract Art Exhibition; Japan and U.S.A. at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (April 29–June 12, 1955), neither of which feature circles in any significant way. Where, then, did the idea to create canvases consisting only of circles come from?

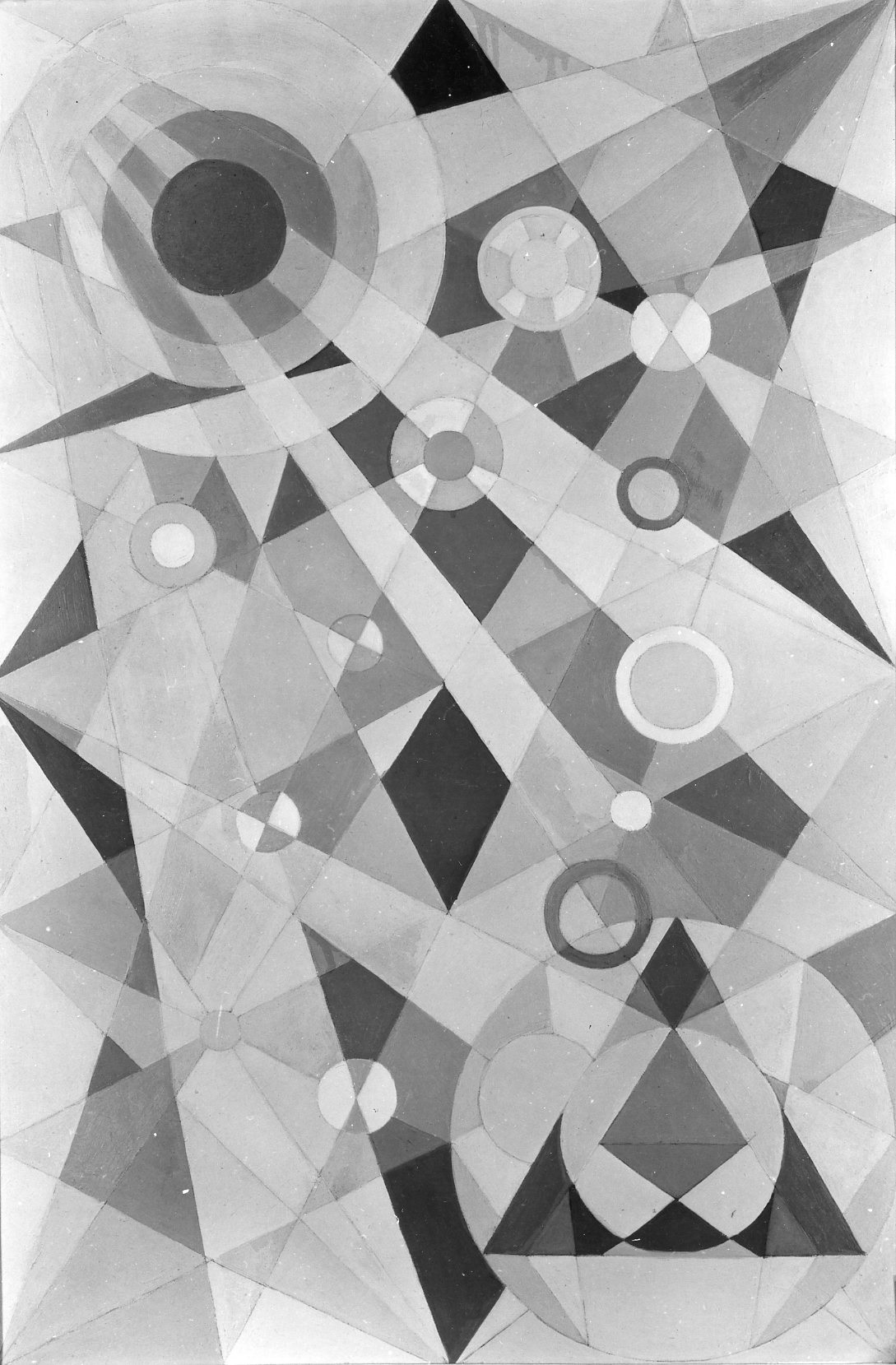

In the artworks of the other artists exhibited as part of the Abstract Art Exhibition; Japan and U.S.A., it is hard to see any works that might have influenced Onosato in this regard. The exhibition brought together the work of the American Abstract Artists group formed in 1936 with artwork from Japanese abstract artists, with the work of Hasegawa Saburo playing a key intermediary role between the two sides. The American works exhibited were primarily geometric, but also showed a broader range, with some pieces tending towards Abstract Expressionism. Meanwhile, on the Japanese side, in addition to structuralist pieces by Murai Masanari, Yamaguchi Takeo et al there were also bokusho—avant-garde or abstract sumi-e or calligraphic—works by Ueda Sokyu and Morita Shiryu, providing a sense of originality. Writing in the museum newspaper Gendai no me [Contemporary eye] Elisa Grilli, art critic at The Japan Times at the time, praised this calligraphic leaning, while also admonishing the Japanese side for following in the footsteps of the geometric abstraction of the West. She makes particular mention of Charmion von Wiegandfs Ray of Creation (Fig 4.), holding no punches as she declares that gthis style of geometrical abstraction has been pursued exhaustively in the West, and there is no need for Japanese artists to mine any longer this scanty vein which doesnft fit with the Japanese character.(i)h Yet if this position that, rather than imitating Western trends, Japanese artists should seek to grow their features as Japanese artists, is relatable, it could also be riposted that in subsequently carrying geometrical abstraction to its limits, Onosato overcame the East-West divide and arrived at a form of art with a truly universal quality; if we accept this, then it would seem we need to also be wary of invoking stereotypical tropes of Western and Eastern styles of expression. Either way, of the works exhibited, it was von Wiegandfs Ray of Creation, formed as it was of geometrical straight lines and several circles, that drew the closest to Onosatofs future direction, comparatively speaking. Yet it would be premature to conclude therefore that Onosato was directly inspired by this work. Von Wiegandfs work conveys the powerful intention to create a sense of rhythmicality through an interplay between the lines crossing the canvas diagonally and the circles positioned at their points of intersection, and there is thus a major discrepancy between it and Onosatofs Twelve Circles, where circles are simply repeated horizontal and vertically. We would be better to think that Onosato was led to Twelve Circles not as the result of some external influence, but rather of an internal quest.

Onosato himself, looking back to his creation of this work six years on in 1961, says the following:

That was my very earliest circle work. The circle came to take up its place in my mind in a flash. I was searching for something clear-cut, stripped of any excess. Yet for a while, I couldnft think of anything that met that description. Then the idea came to me of simply placing circles in lines, and to my surprise, that idea totally occupied me. It was something entirely my own. (ii)

Something in a similar vein is a poetic passage introduced in her Onosato Toshinobu den [The Life of Onosato Toshinobu] by Onosato Tomoko:

On the way home from the train window

Circles of the same size evenly spaced

In a line a thought came to me

That idea came in a single instant

Just so much was it something

Entirely of my own

Onosato Toshinobu, 1961 (iii)

If we trust these accounts, we see that the idea of creating canvases made up only of circles was something that came to the artist in a flash, much like a revelation. In the second quotation, we find the suggestion that this something occurred to him while looking at something from the train window—and yet it would seem that said flash could come only have come to him after his experiences with experimental abstraction that he had been pursuing for several years

(iv).

That said, it is also true that Twelve Circles is somewhat different to the series of flat circle paintings that succeeded it. For a start, although the circles were positioned with rough regularity, with three lengthways and four vertically, this placement was not exact. There was some variation, and in particular, the three circles occupying the second row from the bottom veer slightly to the left. Further, nine of the twelve circles are not flat circles, but rather have two layers, most of whose centers are slightly divergent. Accordingly, the circles resemble eyeballs, directing their gaze in various directions. The circles in each of the four corners are directing their gaze into the center of the canvas, while the second from the top on the right and the section from the bottom on the left are looking outside the canvasfs borders. Resultantly, the work strikes a delicate balance between centripetal and centrifugal force, and appears to the viewer to vibrate. Then there is the coloration to mention. I would like to focus on red, which would go onto become Onosatofs key color. To the left of the canvas, red is used as the background color, while on the right side of the canvas, it is used rather for the circles; balance is maintained while functions are alternated.

As all this suggests, the composition of Twelve Circles entails some careful maneuvering. In this, it differs from Onosatofs subsequent paintings, whose strictly systematic division between circles and lines engenders the sense of gazing into the laws of the cosmos themselves; in terms of what this says about the artistfs intentions regarding composition, it suggests that Twelve Circles was created at a time when Onosato was at a transitional point. Subsequently, Onosato would move even further in the direction of towards pursuing gsomething clear-cut, stripped of any excess.h We could thus call Twelve Circles a milestone on that long road.

Figures

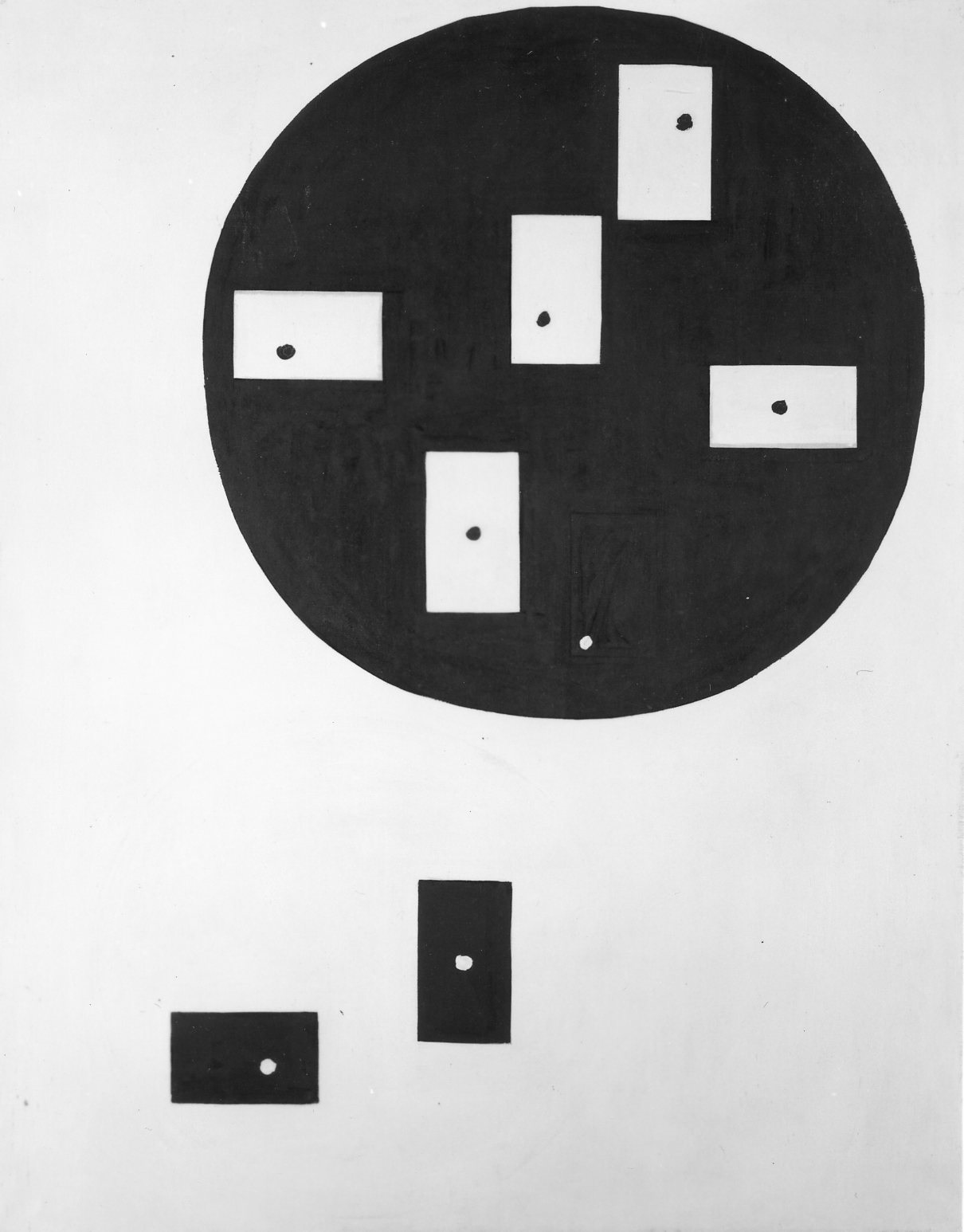

1. Onosato Toshinobu, Black and White Circles, 1940

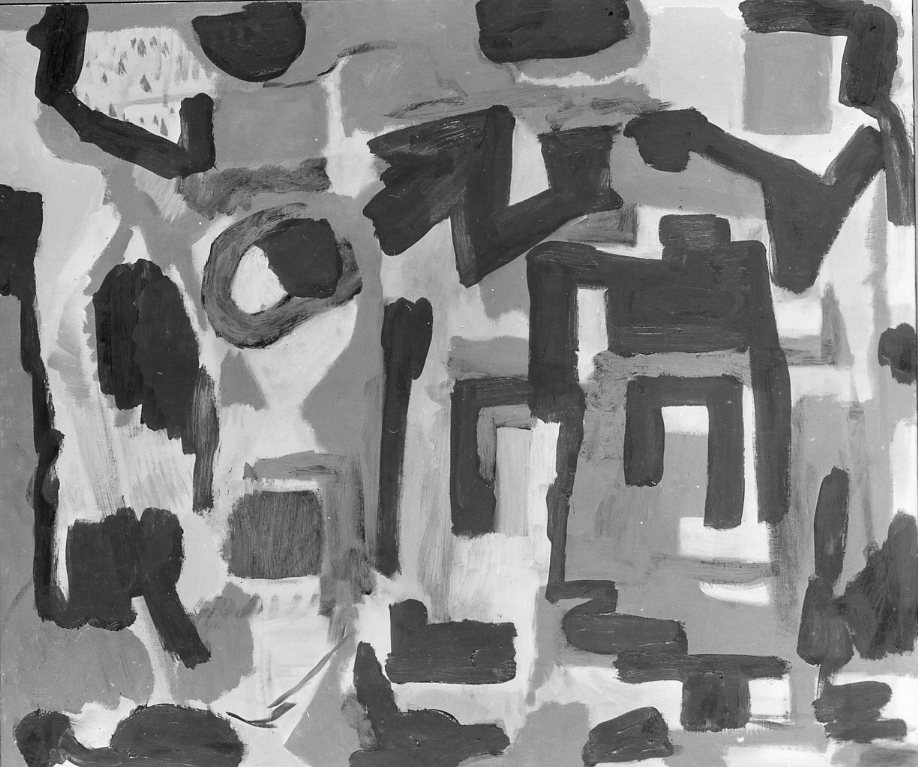

2. Onosato Toshinobu, Appearance, 1954

3. Onosato Toshinobu, Rhinoceros Beetle, 1955

4. Charmion von Wiegand, Ray of Creation

i: Elisa Grilli, gA Comparison of Japanese and American Abstract Arth, Gendai no me, Issue 7, June 1955, p.4.

ii: Onosato Toshinobu, gMy Circles—The Return Journey from Figurative to Abstract,h Bijutsu Journal, Issue 18, March 1961, p. 16

iii: Onosato Tomoko, Onosato Toshinobu den [The Life of Onosato Toshinobu], Art Space, December 1991, p.192

iv: In 1958, Onosato stated the following about the appearance of circles in his work: geIt is in the last two or three years that circles have begun to appear in my work as a clear-cut image, yet my interest in the circle didnft appear suddenly, but has rather been smoldering within me for the last fifteen years or so. [c] In the last four or five years, along with a certain calming of my feelings has come a clarification of the issues relating to my work, and the groundwork was thus laid in my consciousness for the appearance of the circles. And then, with extreme suddenness, they appeared as a clear-cut image.h (Onosato Toshinobu, geCirclesf and eEggsf—the Circle-Drawing Poultry Farmerh, Geijutsu Shincho, Vol. 9 Issue 7, July 1958, p.225.)

|