瀧口修造 人と作品

土渕信彦

詩人、美術評論家として知られる瀧口修造は、シュルレアリスム運動を日本に導入し、前衛芸術運動の理論的・精神的支柱として、戦前・戦後を通じ多くの芸術家の活動を鼓舞し続けた。数々の前衛的な詩作品を発表し、内外の造形作家とも詩画集を共作しただけでなく、自らも多数の造形作品を制作している。以下、その生涯を簡単に振り返り、造形の仕事について解説する。

生涯:1903年、富山県婦負(ねい)郡寒江(さむえ)村大塚(現在の富山市大塚)の、代々十村役(とむらやく)(名主)務めてきた旧家に、父四郎、母たきの長男(第3子)として生まれた。1915年に父が他界し、祖父の代から続く医院の継承を期待されたが、短歌や象徴詩、美術書に親しみ、ことに白樺派やウィリアム・ブレイクを愛読していた。母の没した翌年(1923年)、美学を志望して慶應義塾大学文学部予科に入学したものの授業に失望し、また関東大震災で学資も失って退学した。長姉をたよって小樽に渡り、小学校の代用教員などの職を探したが、結局、姉の強い勧めと援助により25年に慶應義塾に復学し、英文科在学中に西脇順三郎教授を通じてシュルレアリスムを知った。『超現実主義宣言』『磁場』などを読んで深く傾倒、今日では日本の前衛詩の極北と見なされている一連の実験的な詩的テクストを発表し、30年にはブルトン『超現実主義と絵画』(初版)も全訳した。

31年に卒業後、映画製作所PCL(写真化学研究所。東宝の前身)にスクリプターとして勤務する傍ら、美術評論活動を開始した。海外のシュルレアリストたちと文通を続け、ブルトン『通底器』、『狂気の愛』、「文化擁護作家会議における講演」やエルンスト、ダリの著作なども翻訳している。37年には山中散生とともに「海外超現実主義作品展」を開催し、記念出版『アルバム・シュルレアリスト』も編集した。「超現実造型論」「超現実主義の現代的意義」などの美術評論だけでなく「物体と写真」などの写真評論も執筆し(38年の『近代芸術』に集成された)、さらには研究・発表グループも組織して、画壇に属さない前衛美術家・写真家たちを理論的に指導した。しかし、こうした活動は(皮肉なことに)国際共産主義運動に関係する危険なものと見なされて、41年春から7ヶ月余り特高によって逮捕・拘留され、中断を余儀なくされた。

戦後は『読売新聞』などに多くの美術評論を発表し、「時代の証言者」とも評される代表的な美術評論家として活動した。タケミヤ画廊の企画を委嘱され、208回に及ぶ展覧会を開催して、多数の若手美術家に発表の機会を設ける一方、51年に結成された「実験工房」の活動にも顧問格として関与するなど、清廉な人柄も相俟って影響力は絶大であった。58年、ヴェネチア・ビエンナーレのコミッショナーとして訪欧、イタリアの彫刻部門の代表フォンタナを高く評価して絵画部門で票を投じた後、欧州各地を訪問し、ブルトン、デュシャン、ダリ、ミショーらと面会した(ブルトンとの会談を自ら「生涯の収穫」と回想)。帰国後、時評的な美術評論の発表が減少する一方、展覧会序文などの私的な執筆が増加した。公的な役職を辞任する反面、赤瀬川原平の「千円札事件」(65~70年)では特別弁護人を引き受けて芸術の自由を主張した。

ミロ、サム・フランシス、アントニ・タピエスなど、多くの造形作家と詩画集を共作したほか、自らもドローイング、水彩、デカルコマニー、吸取紙作品、バーント・ドローイング(焼け焦がした水彩)、ロトデッサン(モーターによる回転描線)などの、独特な手法の造形作品を制作し、60年から71年にかけて個展も4回開催している。67年には戦間期の詩的テクストを集成した『瀧口修造の詩的実験 1927~1937』を刊行した。夢の記録の形をとった散文作品や、諺のような短いフレーズの作品も残している。

60年代初頭に、コンセプチュアルな「オブジェの店」の開業を構想し、「ローズ・セラヴィ」と命名することを、上記の訪欧後も文通を続けていたデュシャンから許可された。この返礼に68年に『マルセル・デュシャン語録』を刊行、その後もデュシャン研究を継続し、77年には「大ガラス」の一部を立体化したマルティプル『檢眼圖』も制作している(造形作家岡崎和郎との共作)。79年に心筋梗塞のため没した。

造形:造形領域の仕事は、主に欧州旅行からの帰国後の60年頃に開始され、70年代まで継続されている(50年代の作品も数点ある)。正確な点数は不明だが、合計1千点を超えるかもしれない。60年代後半と70年代中期以降の年記のある作品はあまり眼にしないようだが、この時期は『マルセル・デュシャン語録』の制作や「千円札事件」の弁護、上述のデュシャン研究などに注力していたためだろう。制作状況や点数の詳細は、今後の研究に俟ちたい。制作の背景や過程については、別掲の「私も描く」(61年)、「手が先き、先きが手」(74年)などに述べられている。以下、簡単に付言する。

① インク・ドローイングから開始され、2~3年の短期間のうちに水彩、デカルコマニー、吸取紙作品、バーント・ドローイング、ロトデッサンなど、独特の多彩な手法に展開された。油彩は57年(訪欧前)の例外的な小品2点のみで、ドローイングは油彩などの下書きではない。

② 用いられた材料はさまざまで、インク、墨、水彩絵具、エナメルなど。支持体では画用紙、艶紙、吸取紙など。ロトデッサンではサンドペーパーが用いられることもある。筆記用具では万年筆、ボールペン、割箸、各種の筆、スポンジなど。

③ 当初の制作の動機は、意図や恣意を極力排し線の自発性に委ねながら、イメージと文字とが分離する瞬間を見極めること、ないしイメージに意味が宿り得るかを試すことのように思われ、戦後の瀧口が抱いていた、前衛書道やカリグラフィックな傾向の作家たち、アンフォルメル運動などへの関心にも沿っているようである。さらに遡って、30年に翻訳し後の美術評論でも引用していた、『超現実主義と絵画』のイメージの固定化と言語の形成をめぐる一節(『コレクション瀧口修造』11巻182頁 みすず書房)に淵源するとも考えられよう。

④ 展開された造形の多様性は、多彩な材料・支持体・筆記用具の特性や火と水の作用を活かしながら、差異が付加されていった結果と思われ、造形自体の論理というよりは(差異の体系である)言語の論理に従っているとも考えられる。ドローイングや水彩がデカルコマニーに収束していったのは、おそらくイメージの瞬間的な出現と定着への志向によるものだろう。

⑤ こうして得られた作品は、伝統的な(構想・配列・措辞に基づく)制作や作品の概念を逸脱した、行為の余剰ないし証拠品と位置付けられているようである。といっても作品を作る意図や志向が無いわけではなく、展覧会の開催、サインや年代の記載などの事実がそれを証拠付けている。60年9月の最初の個展(南天子画廊)の自序の冒頭一節「プエブロ・インディアンたちは砂の上に絵を描きます」は(同4巻75頁)、西洋絵画の伝統に根差さない制作への志向を示唆するものかもしれない。実際、1970年頃に制作された黒色のデカルコマニーは、東洋の水墨画を想起させるところがある。

⑥ 台紙に貼る形も作品化への志向を物語っているだろう。この形はバーント・ドローイングやロトデッサンで採用され、少数ながら吸取紙作品でも確認される。デカルコマニーも、存命中に展示ないし友人たちに贈呈された作品は、台紙に貼られ額装されている。吸取紙作品とバーント・ドローイングは、伝統的な制作や作品の概念に収まらず、物体性も強いことから、(平面ではあるが)オブジェと位置付けられているとも考えられる。吸取紙作品については瀧口自身による次のような英文のメモが残されている。“Blotting paper is something. / It remains by itself. / It is this now. / I will keep it.”

⑦ 瀧口の作品の、他の作家の作品との類似性は(例えばミショー、ポロック、デュシャン、ティンゲリー、マン・レイ、フォンタナ、イヴ・クラインなど)、彼らとの対話に基づくある種の引用とも考えられる。視野の広い評論活動の成果といえるだろう。

以上総じて、瀧口の造形作品からは、美術批評の仕事から解放され、若き日に熱中していたシュルレアリスムを再び生き、楽しそうに制作に没頭する姿が窺える。自らの時間と熱意、さらには永年にわたる評論活動の精髄までも注ぎ込まれた、後半生の中心的仕事と考えられよう。

Shuzo Takiguchi ― Life and Works

Nobuhiko Tsuchibuchi

Known for his work as a poet and art critic, Shuzo Takiguchi devoted great energy to introducing and promoting the spread of surrealism, with which he had been fascinated in his younger days, in Japan. Through his role in providing support for the avant-garde movement, both through his critical activities and as a mentor figure, he fostered the development of many artists before and after the war. He was responsible for producing not only dozens of experimental poetic works and several collaborative projects with visual artists from both Japan and overseas, but also much artwork of his own. Here, I shall provide a brief overview of his life, and consider the range of artistic work he produced.

Life : Shuzo Takiguchi was born in 1903, in Otsuka in Toyama Prefecture, into a family whose members had served as village chiefs for generations, as the third child to Shiro and Taki Takiguchi. In 1915, his father Shiro passed away. As the only son, he was expected to take over the family medical practice set up by his grandfather, but he was already more at home in the world of tanka, symbolist poetry and art books, in particular, he loved the Shirakaba literary coterie and the work of William Blake. In 1923, the year after his mother died, he entered a preparatory course at Keio University to study aesthetics, but dropped out midway through the year, finding the lectures disappointing, and also losing his school expenses after the Great Kanto Earthquake on 1st September. He moved to Otaru in Hokkaido Prefecture, where his elder sister lived, to get a job as a substitute teacher at elementary school. In 1925, he entered Keio University once again, this time to study literature. It was here that he discovered surrealism, through Junzaburo Nishiwaki, a professor as well as a poet. Takiguchi was profoundly affected by works such as Surrealist Manifesto and The Magnetic Fields, and published a series of experimental poetic texts of his own, which are nowadays considered as the pinnacle of Japanese avant-garde poetry. In 1930, he translated the full text of André Breton’s Surrealism and Painting (first edition).

After graduating in 1931, he began work as a scriptwriter at the movie production company, PCL (the forerunner to Toho Co. Ltd), also beginning his activity as an art critic on the side. He maintained a correspondence with surrealist artists overseas, translating pieces such as Breton’s Communicating Vessels, Mad Love, 'Lecture at the International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture' as well as essays by Max Ernst and Salvador Dali. In 1937, together with Chiryu (Tiroux) Yamanaka, he organized an exhibition of surrealist works from overseas, publishing the Album Surréaliste to coincide with the exhibition. Not only publishing many critical works concerned with art and photography, such as 'A Theory of Surrealist Art', 'The Contemporary Significance of Surrealism' and 'Objects and Photographs' (all in Kindai Geijutsu (Modern Art), 1938), but also organizing several theoretical study groups in the fields of art and photography, Takiguchi continued to lead and inspire the avant-garde movement. However, these activities were condemned, ironically enough, as liable to contribute to the spread of communism. He was arrested and detained for a period of seven months from the spring of 1941 onwards, forcing him to give up his voluntary critical work.

After the war, Shuzo Takiguchi contributed a large amount of writing to newspapers and art magazines such as the Yomiuri Shimbun. He was seen as one of the leading art critics of his day, and a spokesperson of the age. In charge of planning shows for the Takemiya Gallery, he organized a grand total of 208 exhibitions for many young artists to display their works. He also served as a mentor figure for the Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop) interdisciplinary artistic group established in 1951. These activities, together with his great sense of personal integrity, ensured he had huge influential power on the scene at the time. In 1958, he visited Europe to serve as Commissioner in the Venice Biennale, encountering the work of the Italian sculptor Fontana that he rated most highly and voted for the painting prize. He then went on to travel around Europe where he met Breton, Duchamp, Dali, Michaux and others―he referred to his meeting with Breton as 'the harvest of my lifetime'. After he returned to Japan, he began writing less and less art criticism, though his involvement in his own private writing projects, such as penning the introductions to exhibitions and so on, increased. While generally giving up on his role as public figure, he nonetheless agreed to serve as a special defence pleader championing the freedom of the arts in the 1965-1970 court case where Genpei Akasegawa was indicted for printing fake 1000 yen bills (the artist insisted that the bills were “not fakes but models”).

As well as collaborating with visual artists such as Joan Mirò, Sam Francis, Antoni Tàpies and others in the publication of artists’ books, he also produced artwork of his own using a variety of special methods such as drawing, watercolours, decalcomania, works with blotting paper, 'burnt drawings' (drawings burnt with a flame), and 'roto-dessins' (drawings of concentric circles using a revolving motor). Between 1960 and 1971, he had four exhibitions of his own. In 1967 he published Shuzo Takiguchi’s Poetic Experiments 1927-1937, a collection of his poetic texts, followed by intermittent prose describing his dreams and short proverb-like phrases.

At the beginning of the 1960s, Takiguchi came up with the idea of opening a conceptual object shop, and was permitted to name it Rrose Sélavy from Marcel Duchamp, with whom he kept up a correspondence with after his trip to Europe. As a mark of gratitude to the artist, he published his book To and From Rrose Sélavy in 1968, and continued studying the artist. He issued the multiple edition of 100, Oculist Witnesses, an objet made in collaboration with the artist Kazuo Okazaki that transferred into three dimensions a section of Duchamp’s Large Glass. He died in 1979 of myocardial infarction.

Artwork: Shuzo Takiguchi's forays into the visual art sphere were mostly executed after his trip to Europe―more accurately, they begun in 1960, and continued into the 1970s, although there are some exceptions produced in the 1950s. The exact total number of works he produced is not known, but it may well be over a thousand. We don’t see many works in the late 1960s or the mid-1970s onwards, when he was involved in producing To and From Rrose Sélavy, serving as a defence pleader in the 1000-yen bills trial, or pouring his energies into Duchamp- related tasks. The precise number of works and the production method deserve more rigorous research in the future. Takiguchi himself referred to his work and creation process in the essays 'I Also Draw' and 'First-hand Experiences' featured in this volume. Below are some brief additional points to be noted.

① Takiguchi's experiments began with ink drawings. In the course of a few years, he expanded to using wide range of techniques such as watercolours, decalcomania, blotting paper works, burned drawings, roto-dessins, and so on. It should be noted that his drawings were not preparatory studies for oils.

② Takiguchi used a wide variety of materials―writing ink, Indian ink, watercolours, enamel and so on―as well as a range of different types of paper: sugar paper, glossed paper, blotting paper and similar. In his roto-dessins, he occasionally used sandpaper. His drawing instruments were similarly assorted: fountain pens, ball pens, disposable chopsticks, sponges etc.

③ Takiguchi's motives for beginning his experiments in drawing would appear to be to investigate the moment when the formation of letters became separate from the image, or, alternatively, when the image imbues itself with meaning, doing his best to put aside all intention and abandoning himself to the spontaneity of the lines. His experiments also came together with his interest in avant-garde calligraphy in Japan and calligraphic paintings, as well as the Art Informel movement. It is also possible to trace it back to a passage in Breton’s Surrealism and Painting, that he translated in 1930 and later quoted in some important essays, about the consolidation of the image and the formation of language.

④ The diversity of Takiguchi's works could be said to be the result of his fascination with perpetually varying the work he produced, making the most of the distinctive features of materials, papers and instruments, and incorporating fire and water. This perpetual variation appears to come less out of consideration of the logic of visual arts than that of the logic of language―the system of differences. The fact that his decalcomania eventually took the place of his drawings and watercolours was almost certainly out of the intention to move towards the momentarily appearing and the persisting image.

⑤ Takiguchi viewed his works as what was left over from the act, or else, the proof of it work. In other words, his work didn’t follow traditional conceptions of the creative process and artwork itself that were based on ideas of plans, arrangement and syntax. Yet it was not as though the works he produced were strictly without purpose or intention, as illustrated by the fact that he signed and dated his works, as well as by the fact that he showed his work in exhibitions. The opening line to the introductory text written for his first solo exhibition in September 1960, “The Pueblo Indians draw pictures on the sand,” is quite possibly suggestive of the inclination towards making work that doesn’t have its roots in the painting traditions of the West. In fact, his decalcomania works in black circa 1970 often remind us of Oriental Indian ink paintings (sumi-e).

⑥ The fact that Takiguchi mounted his pieces also indicates an intention on his part to make them into works of art. This is frequently seen in the case of his burnt drawings and roto-dessins. Some of his blotting paper works have also been mounted, although fewer of these. Those decalcomania works that were exhibited during his lifetime or given to his friends as presents were stuck to a cardboard mount and framed. Unrestricted by the traditional conception of artistic creation and artwork, his blotting paper works and burnt drawings could be regarded by the artist as objets in virtue of their strong physical sense, despite their being two-dimensional. On his blotting paper works, he jotted this memorandum in English. “Blotting paper is something. / It remains by itself. / It is this now. / I will keep it.”

⑦ The similarity between Takiguchi’s works and those of other artists (Michaux, Pollock, Duchamp, Jean Tinguely, Man Ray, Fontana, Yves Klein and so on) could be seen as a kind of citation that stems from his dialogue with them. It seems appropriate to call it the fruit of his wide-ranging critical activity.

From all the above, a picture emerges of Takiguchi as the artist as someone liberated from his role as an art critic―someone enjoying immersion in his creation as a way of reliving the surrealism he had immersed himself in in his younger days. We can see his artwork as the central endeavour of the later half of his life, into which he poured his time and energy, as well as the very essence of his years of critical experience.

Translated by Polly Barton

*『瀧口修造展 I』図録より再録

◆ときの忘れものは2014年1月8日[水]―1月25日[土]「瀧口修造展 Ⅰ」を開催しています。

2014年、3回に分けてドローイング、バーントドローイング、ロトデッサン、デカルコマニーなど瀧口修造作品を展示いたします(1月、3月、12月)。

2014年、3回に分けてドローイング、バーントドローイング、ロトデッサン、デカルコマニーなど瀧口修造作品を展示いたします(1月、3月、12月)。

このブログでは関係する記事やテキストを「瀧口修造の世界」として紹介します。土渕信彦のエッセイ「瀧口修造の箱舟」と合わせてお読みください。

●カタログのご案内

<お送りいただいたカタログは昨日こちらへ無事に届きました。どうもありがとうございました。スタイリッシュで読みやすく、すばらしい書物となったように思います。>(Pさんより)

『瀧口修造展 I』図録

『瀧口修造展 I』図録

2013年

ときの忘れもの 発行

図版:44点

英文併記

21.5x15.2cm

ハードカバー

76ページ

執筆:土渕信彦「瀧口修造―人と作品」

再録:瀧口修造「私も描く」「手が先き、先きが手」

価格:2,100円(税込)

※送料別途250円(お申し込みはコチラへ)

●瀧口修造 Shuzo TAKIGUCHIの出品作品を順次ご紹介します。

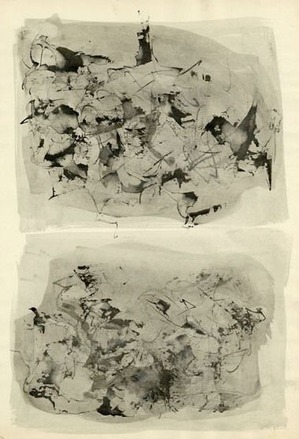

瀧口修造 Shuzo TAKIGUCHI

「出品番号 I-33」

水彩、インク、紙

イメージサイズ:35.7×25.0cm

シートサイズ :35.7×25.1cm

瀧口修造 Shuzo TAKIGUCHI

「出品番号 I-34」

水彩、インク、紙

イメージサイズ:34.2×23.6cm

シートサイズ :35.7×25.1cm

こちらの作品の見積り請求、在庫確認はこちらから

土渕信彦

詩人、美術評論家として知られる瀧口修造は、シュルレアリスム運動を日本に導入し、前衛芸術運動の理論的・精神的支柱として、戦前・戦後を通じ多くの芸術家の活動を鼓舞し続けた。数々の前衛的な詩作品を発表し、内外の造形作家とも詩画集を共作しただけでなく、自らも多数の造形作品を制作している。以下、その生涯を簡単に振り返り、造形の仕事について解説する。

生涯:1903年、富山県婦負(ねい)郡寒江(さむえ)村大塚(現在の富山市大塚)の、代々十村役(とむらやく)(名主)務めてきた旧家に、父四郎、母たきの長男(第3子)として生まれた。1915年に父が他界し、祖父の代から続く医院の継承を期待されたが、短歌や象徴詩、美術書に親しみ、ことに白樺派やウィリアム・ブレイクを愛読していた。母の没した翌年(1923年)、美学を志望して慶應義塾大学文学部予科に入学したものの授業に失望し、また関東大震災で学資も失って退学した。長姉をたよって小樽に渡り、小学校の代用教員などの職を探したが、結局、姉の強い勧めと援助により25年に慶應義塾に復学し、英文科在学中に西脇順三郎教授を通じてシュルレアリスムを知った。『超現実主義宣言』『磁場』などを読んで深く傾倒、今日では日本の前衛詩の極北と見なされている一連の実験的な詩的テクストを発表し、30年にはブルトン『超現実主義と絵画』(初版)も全訳した。

31年に卒業後、映画製作所PCL(写真化学研究所。東宝の前身)にスクリプターとして勤務する傍ら、美術評論活動を開始した。海外のシュルレアリストたちと文通を続け、ブルトン『通底器』、『狂気の愛』、「文化擁護作家会議における講演」やエルンスト、ダリの著作なども翻訳している。37年には山中散生とともに「海外超現実主義作品展」を開催し、記念出版『アルバム・シュルレアリスト』も編集した。「超現実造型論」「超現実主義の現代的意義」などの美術評論だけでなく「物体と写真」などの写真評論も執筆し(38年の『近代芸術』に集成された)、さらには研究・発表グループも組織して、画壇に属さない前衛美術家・写真家たちを理論的に指導した。しかし、こうした活動は(皮肉なことに)国際共産主義運動に関係する危険なものと見なされて、41年春から7ヶ月余り特高によって逮捕・拘留され、中断を余儀なくされた。

戦後は『読売新聞』などに多くの美術評論を発表し、「時代の証言者」とも評される代表的な美術評論家として活動した。タケミヤ画廊の企画を委嘱され、208回に及ぶ展覧会を開催して、多数の若手美術家に発表の機会を設ける一方、51年に結成された「実験工房」の活動にも顧問格として関与するなど、清廉な人柄も相俟って影響力は絶大であった。58年、ヴェネチア・ビエンナーレのコミッショナーとして訪欧、イタリアの彫刻部門の代表フォンタナを高く評価して絵画部門で票を投じた後、欧州各地を訪問し、ブルトン、デュシャン、ダリ、ミショーらと面会した(ブルトンとの会談を自ら「生涯の収穫」と回想)。帰国後、時評的な美術評論の発表が減少する一方、展覧会序文などの私的な執筆が増加した。公的な役職を辞任する反面、赤瀬川原平の「千円札事件」(65~70年)では特別弁護人を引き受けて芸術の自由を主張した。

ミロ、サム・フランシス、アントニ・タピエスなど、多くの造形作家と詩画集を共作したほか、自らもドローイング、水彩、デカルコマニー、吸取紙作品、バーント・ドローイング(焼け焦がした水彩)、ロトデッサン(モーターによる回転描線)などの、独特な手法の造形作品を制作し、60年から71年にかけて個展も4回開催している。67年には戦間期の詩的テクストを集成した『瀧口修造の詩的実験 1927~1937』を刊行した。夢の記録の形をとった散文作品や、諺のような短いフレーズの作品も残している。

60年代初頭に、コンセプチュアルな「オブジェの店」の開業を構想し、「ローズ・セラヴィ」と命名することを、上記の訪欧後も文通を続けていたデュシャンから許可された。この返礼に68年に『マルセル・デュシャン語録』を刊行、その後もデュシャン研究を継続し、77年には「大ガラス」の一部を立体化したマルティプル『檢眼圖』も制作している(造形作家岡崎和郎との共作)。79年に心筋梗塞のため没した。

造形:造形領域の仕事は、主に欧州旅行からの帰国後の60年頃に開始され、70年代まで継続されている(50年代の作品も数点ある)。正確な点数は不明だが、合計1千点を超えるかもしれない。60年代後半と70年代中期以降の年記のある作品はあまり眼にしないようだが、この時期は『マルセル・デュシャン語録』の制作や「千円札事件」の弁護、上述のデュシャン研究などに注力していたためだろう。制作状況や点数の詳細は、今後の研究に俟ちたい。制作の背景や過程については、別掲の「私も描く」(61年)、「手が先き、先きが手」(74年)などに述べられている。以下、簡単に付言する。

① インク・ドローイングから開始され、2~3年の短期間のうちに水彩、デカルコマニー、吸取紙作品、バーント・ドローイング、ロトデッサンなど、独特の多彩な手法に展開された。油彩は57年(訪欧前)の例外的な小品2点のみで、ドローイングは油彩などの下書きではない。

② 用いられた材料はさまざまで、インク、墨、水彩絵具、エナメルなど。支持体では画用紙、艶紙、吸取紙など。ロトデッサンではサンドペーパーが用いられることもある。筆記用具では万年筆、ボールペン、割箸、各種の筆、スポンジなど。

③ 当初の制作の動機は、意図や恣意を極力排し線の自発性に委ねながら、イメージと文字とが分離する瞬間を見極めること、ないしイメージに意味が宿り得るかを試すことのように思われ、戦後の瀧口が抱いていた、前衛書道やカリグラフィックな傾向の作家たち、アンフォルメル運動などへの関心にも沿っているようである。さらに遡って、30年に翻訳し後の美術評論でも引用していた、『超現実主義と絵画』のイメージの固定化と言語の形成をめぐる一節(『コレクション瀧口修造』11巻182頁 みすず書房)に淵源するとも考えられよう。

④ 展開された造形の多様性は、多彩な材料・支持体・筆記用具の特性や火と水の作用を活かしながら、差異が付加されていった結果と思われ、造形自体の論理というよりは(差異の体系である)言語の論理に従っているとも考えられる。ドローイングや水彩がデカルコマニーに収束していったのは、おそらくイメージの瞬間的な出現と定着への志向によるものだろう。

⑤ こうして得られた作品は、伝統的な(構想・配列・措辞に基づく)制作や作品の概念を逸脱した、行為の余剰ないし証拠品と位置付けられているようである。といっても作品を作る意図や志向が無いわけではなく、展覧会の開催、サインや年代の記載などの事実がそれを証拠付けている。60年9月の最初の個展(南天子画廊)の自序の冒頭一節「プエブロ・インディアンたちは砂の上に絵を描きます」は(同4巻75頁)、西洋絵画の伝統に根差さない制作への志向を示唆するものかもしれない。実際、1970年頃に制作された黒色のデカルコマニーは、東洋の水墨画を想起させるところがある。

⑥ 台紙に貼る形も作品化への志向を物語っているだろう。この形はバーント・ドローイングやロトデッサンで採用され、少数ながら吸取紙作品でも確認される。デカルコマニーも、存命中に展示ないし友人たちに贈呈された作品は、台紙に貼られ額装されている。吸取紙作品とバーント・ドローイングは、伝統的な制作や作品の概念に収まらず、物体性も強いことから、(平面ではあるが)オブジェと位置付けられているとも考えられる。吸取紙作品については瀧口自身による次のような英文のメモが残されている。“Blotting paper is something. / It remains by itself. / It is this now. / I will keep it.”

⑦ 瀧口の作品の、他の作家の作品との類似性は(例えばミショー、ポロック、デュシャン、ティンゲリー、マン・レイ、フォンタナ、イヴ・クラインなど)、彼らとの対話に基づくある種の引用とも考えられる。視野の広い評論活動の成果といえるだろう。

以上総じて、瀧口の造形作品からは、美術批評の仕事から解放され、若き日に熱中していたシュルレアリスムを再び生き、楽しそうに制作に没頭する姿が窺える。自らの時間と熱意、さらには永年にわたる評論活動の精髄までも注ぎ込まれた、後半生の中心的仕事と考えられよう。

Shuzo Takiguchi ― Life and Works

Nobuhiko Tsuchibuchi

Known for his work as a poet and art critic, Shuzo Takiguchi devoted great energy to introducing and promoting the spread of surrealism, with which he had been fascinated in his younger days, in Japan. Through his role in providing support for the avant-garde movement, both through his critical activities and as a mentor figure, he fostered the development of many artists before and after the war. He was responsible for producing not only dozens of experimental poetic works and several collaborative projects with visual artists from both Japan and overseas, but also much artwork of his own. Here, I shall provide a brief overview of his life, and consider the range of artistic work he produced.

Life : Shuzo Takiguchi was born in 1903, in Otsuka in Toyama Prefecture, into a family whose members had served as village chiefs for generations, as the third child to Shiro and Taki Takiguchi. In 1915, his father Shiro passed away. As the only son, he was expected to take over the family medical practice set up by his grandfather, but he was already more at home in the world of tanka, symbolist poetry and art books, in particular, he loved the Shirakaba literary coterie and the work of William Blake. In 1923, the year after his mother died, he entered a preparatory course at Keio University to study aesthetics, but dropped out midway through the year, finding the lectures disappointing, and also losing his school expenses after the Great Kanto Earthquake on 1st September. He moved to Otaru in Hokkaido Prefecture, where his elder sister lived, to get a job as a substitute teacher at elementary school. In 1925, he entered Keio University once again, this time to study literature. It was here that he discovered surrealism, through Junzaburo Nishiwaki, a professor as well as a poet. Takiguchi was profoundly affected by works such as Surrealist Manifesto and The Magnetic Fields, and published a series of experimental poetic texts of his own, which are nowadays considered as the pinnacle of Japanese avant-garde poetry. In 1930, he translated the full text of André Breton’s Surrealism and Painting (first edition).

After graduating in 1931, he began work as a scriptwriter at the movie production company, PCL (the forerunner to Toho Co. Ltd), also beginning his activity as an art critic on the side. He maintained a correspondence with surrealist artists overseas, translating pieces such as Breton’s Communicating Vessels, Mad Love, 'Lecture at the International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture' as well as essays by Max Ernst and Salvador Dali. In 1937, together with Chiryu (Tiroux) Yamanaka, he organized an exhibition of surrealist works from overseas, publishing the Album Surréaliste to coincide with the exhibition. Not only publishing many critical works concerned with art and photography, such as 'A Theory of Surrealist Art', 'The Contemporary Significance of Surrealism' and 'Objects and Photographs' (all in Kindai Geijutsu (Modern Art), 1938), but also organizing several theoretical study groups in the fields of art and photography, Takiguchi continued to lead and inspire the avant-garde movement. However, these activities were condemned, ironically enough, as liable to contribute to the spread of communism. He was arrested and detained for a period of seven months from the spring of 1941 onwards, forcing him to give up his voluntary critical work.

After the war, Shuzo Takiguchi contributed a large amount of writing to newspapers and art magazines such as the Yomiuri Shimbun. He was seen as one of the leading art critics of his day, and a spokesperson of the age. In charge of planning shows for the Takemiya Gallery, he organized a grand total of 208 exhibitions for many young artists to display their works. He also served as a mentor figure for the Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop) interdisciplinary artistic group established in 1951. These activities, together with his great sense of personal integrity, ensured he had huge influential power on the scene at the time. In 1958, he visited Europe to serve as Commissioner in the Venice Biennale, encountering the work of the Italian sculptor Fontana that he rated most highly and voted for the painting prize. He then went on to travel around Europe where he met Breton, Duchamp, Dali, Michaux and others―he referred to his meeting with Breton as 'the harvest of my lifetime'. After he returned to Japan, he began writing less and less art criticism, though his involvement in his own private writing projects, such as penning the introductions to exhibitions and so on, increased. While generally giving up on his role as public figure, he nonetheless agreed to serve as a special defence pleader championing the freedom of the arts in the 1965-1970 court case where Genpei Akasegawa was indicted for printing fake 1000 yen bills (the artist insisted that the bills were “not fakes but models”).

As well as collaborating with visual artists such as Joan Mirò, Sam Francis, Antoni Tàpies and others in the publication of artists’ books, he also produced artwork of his own using a variety of special methods such as drawing, watercolours, decalcomania, works with blotting paper, 'burnt drawings' (drawings burnt with a flame), and 'roto-dessins' (drawings of concentric circles using a revolving motor). Between 1960 and 1971, he had four exhibitions of his own. In 1967 he published Shuzo Takiguchi’s Poetic Experiments 1927-1937, a collection of his poetic texts, followed by intermittent prose describing his dreams and short proverb-like phrases.

At the beginning of the 1960s, Takiguchi came up with the idea of opening a conceptual object shop, and was permitted to name it Rrose Sélavy from Marcel Duchamp, with whom he kept up a correspondence with after his trip to Europe. As a mark of gratitude to the artist, he published his book To and From Rrose Sélavy in 1968, and continued studying the artist. He issued the multiple edition of 100, Oculist Witnesses, an objet made in collaboration with the artist Kazuo Okazaki that transferred into three dimensions a section of Duchamp’s Large Glass. He died in 1979 of myocardial infarction.

Artwork: Shuzo Takiguchi's forays into the visual art sphere were mostly executed after his trip to Europe―more accurately, they begun in 1960, and continued into the 1970s, although there are some exceptions produced in the 1950s. The exact total number of works he produced is not known, but it may well be over a thousand. We don’t see many works in the late 1960s or the mid-1970s onwards, when he was involved in producing To and From Rrose Sélavy, serving as a defence pleader in the 1000-yen bills trial, or pouring his energies into Duchamp- related tasks. The precise number of works and the production method deserve more rigorous research in the future. Takiguchi himself referred to his work and creation process in the essays 'I Also Draw' and 'First-hand Experiences' featured in this volume. Below are some brief additional points to be noted.

① Takiguchi's experiments began with ink drawings. In the course of a few years, he expanded to using wide range of techniques such as watercolours, decalcomania, blotting paper works, burned drawings, roto-dessins, and so on. It should be noted that his drawings were not preparatory studies for oils.

② Takiguchi used a wide variety of materials―writing ink, Indian ink, watercolours, enamel and so on―as well as a range of different types of paper: sugar paper, glossed paper, blotting paper and similar. In his roto-dessins, he occasionally used sandpaper. His drawing instruments were similarly assorted: fountain pens, ball pens, disposable chopsticks, sponges etc.

③ Takiguchi's motives for beginning his experiments in drawing would appear to be to investigate the moment when the formation of letters became separate from the image, or, alternatively, when the image imbues itself with meaning, doing his best to put aside all intention and abandoning himself to the spontaneity of the lines. His experiments also came together with his interest in avant-garde calligraphy in Japan and calligraphic paintings, as well as the Art Informel movement. It is also possible to trace it back to a passage in Breton’s Surrealism and Painting, that he translated in 1930 and later quoted in some important essays, about the consolidation of the image and the formation of language.

④ The diversity of Takiguchi's works could be said to be the result of his fascination with perpetually varying the work he produced, making the most of the distinctive features of materials, papers and instruments, and incorporating fire and water. This perpetual variation appears to come less out of consideration of the logic of visual arts than that of the logic of language―the system of differences. The fact that his decalcomania eventually took the place of his drawings and watercolours was almost certainly out of the intention to move towards the momentarily appearing and the persisting image.

⑤ Takiguchi viewed his works as what was left over from the act, or else, the proof of it work. In other words, his work didn’t follow traditional conceptions of the creative process and artwork itself that were based on ideas of plans, arrangement and syntax. Yet it was not as though the works he produced were strictly without purpose or intention, as illustrated by the fact that he signed and dated his works, as well as by the fact that he showed his work in exhibitions. The opening line to the introductory text written for his first solo exhibition in September 1960, “The Pueblo Indians draw pictures on the sand,” is quite possibly suggestive of the inclination towards making work that doesn’t have its roots in the painting traditions of the West. In fact, his decalcomania works in black circa 1970 often remind us of Oriental Indian ink paintings (sumi-e).

⑥ The fact that Takiguchi mounted his pieces also indicates an intention on his part to make them into works of art. This is frequently seen in the case of his burnt drawings and roto-dessins. Some of his blotting paper works have also been mounted, although fewer of these. Those decalcomania works that were exhibited during his lifetime or given to his friends as presents were stuck to a cardboard mount and framed. Unrestricted by the traditional conception of artistic creation and artwork, his blotting paper works and burnt drawings could be regarded by the artist as objets in virtue of their strong physical sense, despite their being two-dimensional. On his blotting paper works, he jotted this memorandum in English. “Blotting paper is something. / It remains by itself. / It is this now. / I will keep it.”

⑦ The similarity between Takiguchi’s works and those of other artists (Michaux, Pollock, Duchamp, Jean Tinguely, Man Ray, Fontana, Yves Klein and so on) could be seen as a kind of citation that stems from his dialogue with them. It seems appropriate to call it the fruit of his wide-ranging critical activity.

From all the above, a picture emerges of Takiguchi as the artist as someone liberated from his role as an art critic―someone enjoying immersion in his creation as a way of reliving the surrealism he had immersed himself in in his younger days. We can see his artwork as the central endeavour of the later half of his life, into which he poured his time and energy, as well as the very essence of his years of critical experience.

Translated by Polly Barton

*『瀧口修造展 I』図録より再録

◆ときの忘れものは2014年1月8日[水]―1月25日[土]「瀧口修造展 Ⅰ」を開催しています。

2014年、3回に分けてドローイング、バーントドローイング、ロトデッサン、デカルコマニーなど瀧口修造作品を展示いたします(1月、3月、12月)。

2014年、3回に分けてドローイング、バーントドローイング、ロトデッサン、デカルコマニーなど瀧口修造作品を展示いたします(1月、3月、12月)。このブログでは関係する記事やテキストを「瀧口修造の世界」として紹介します。土渕信彦のエッセイ「瀧口修造の箱舟」と合わせてお読みください。

●カタログのご案内

<お送りいただいたカタログは昨日こちらへ無事に届きました。どうもありがとうございました。スタイリッシュで読みやすく、すばらしい書物となったように思います。>(Pさんより)

『瀧口修造展 I』図録

『瀧口修造展 I』図録2013年

ときの忘れもの 発行

図版:44点

英文併記

21.5x15.2cm

ハードカバー

76ページ

執筆:土渕信彦「瀧口修造―人と作品」

再録:瀧口修造「私も描く」「手が先き、先きが手」

価格:2,100円(税込)

※送料別途250円(お申し込みはコチラへ)

●瀧口修造 Shuzo TAKIGUCHIの出品作品を順次ご紹介します。

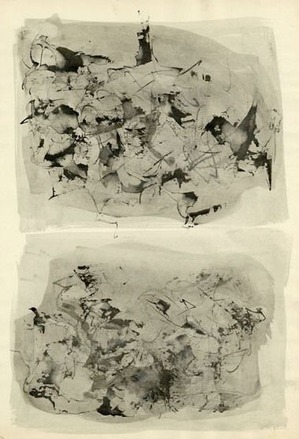

瀧口修造 Shuzo TAKIGUCHI

「出品番号 I-33」

水彩、インク、紙

イメージサイズ:35.7×25.0cm

シートサイズ :35.7×25.1cm

瀧口修造 Shuzo TAKIGUCHI

「出品番号 I-34」

水彩、インク、紙

イメージサイズ:34.2×23.6cm

シートサイズ :35.7×25.1cm

こちらの作品の見積り請求、在庫確認はこちらから

コメント