「没後60年 第29回瑛九展」

新型コロナウイルス感染拡大防止のため、画廊始まって以来初めてのWeb展としてYouTubeでの展示を行います。映像制作は『月刊フリーWebマガジン Colla:J(コラージ)』の塩野哲也さんにご担当いただきました。『まるで実際に画廊で作品を見ているような』リアリティーを追求した動画に仕上がりました。

そして、東京国立近代美術館の大谷省吾先生に本展(Web展)についてご執筆いただきましたので、併せてご覧ください。

*Please scroll down for the English text.

ウェブ上で見る瑛九晩年の点描作品

大谷省吾(東京国立近代美術館美術課長)

今年、2020年は瑛九没後60年にあたる。今回の展覧会は、この節目の年にあわせて晩年の点描作品《ながれ(B)》(1958年)、《赤の舞い》(1958年)、《たそがれ》(1959年)が集められたが、新型コロナウィルスの脅威が広がるなか、予防策としてウェブ上での展覧会となってしまった。実物に対面できないのは残念であるけれども、この機会を逆手にとって、瑛九の点描作品をウェブ上で、つまりパソコンの画面を通して見るという体験そのものに意識を向けてみてはどうだろう。彼の作品を考える上で、決して無意味ではないはずだ。

瑛九は1957年から59年にかけて、小さな丸い形の集合のような抽象作品から、次第に細かな点描作品へと作風を展開させ、その成果を1960年の兜屋画廊における個展(2月23日―28日)で発表した。この個展について、小川正隆は次のような批評を書いている。

「瑛九が6年ぶりの個展を開いている。作品は58年以後のもので、60号から200号までの9点。しかも100号以下の作品は2点しかない。彼は昨年11月から病床についているが『できるだけ早く個展を開きたい…』と熱望しており、友人たちの協力でこんど発表にこぎつけたものだ。

瑛九は日本の前衛絵画の先駆者のひとりだが、画壇を舞台に派手な活躍をしなかったせいか、その仕事はあまり知られていない。が、こんどの制作を見ていると、その仕事の厚味とでもいうか、誠実に追求をつづけてきた抽象絵画の、彼なりの一里ヅカを築き上げたという気がする。様式にいえば、ひとつのアンフォルメルの流れに属するだろうが、黄、青、緑、オレンジ……のこまかい色点で描き上げてゆく画面は、的確な秩序――色彩と構成の精巧な計算からなっている。

衝動的、直情的なアンフォルメル一般の仕事とは、まったく本質は逆のものだ。冷静に色点を操作しながら、新鮮な幻想を織り込んだ、かなり動きのある空間を生み出している。ユニークな仕事である。自然のイメージを感じさせる『田園』、神秘的な光と空間を描いた『流れ―れいめい』など。みごとな労作といえよう」(註1)。

この批評で興味深いのは、瑛九の点描作品を、アンフォルメルと比較して論じている点である。1950年代初頭から少しずつ日本に紹介されていたこの動向は、1956年の「世界・今日の美術展」で大きな注目を集め、1957年にこの動向の仕掛人である批評家ミシェル・タピエが来日することにより、「アンフォルメル旋風」とまで呼ばれる大流行が巻き起こることとなった。言葉としては「非定形」「不定形」「無形象」を意味するアンフォルメルだが、日本の作家たちに与えた影響という点では、加藤瑞穂が指摘する通り、行為と物質に目を向けさせたことが重要である(註2)。その点では小川の展評は正しい。たしかに瑛九の点描作品は、様式としては「不定形」であるけれども「衝動的、直情的なアンフォルメル一般の仕事とは、まったく本質は逆のもの」といえるだろう。ではその瑛九の点描作品の「本質」とは何かということが問題になる。

瀬尾典昭は瑛九晩年の点描作品の展開について、次のような5つのパターンに分類している(註3)。

1 大きな丸と小さな丸とが入れ子状態で同心円が形作られる作品

2 花火とよばれる少し大きめの丸の周辺に発光するようなギザギザの輪が取り囲む作品

3 小石のような色丸がびっしり画面を蔽い尽くす作品

4 跡を引くような筆触で消失点から弾けるように外に向かってながれる動きがある作品

5 微細な点描が登場する最後の画面

今回の出品作を当てはめるならば、《赤の舞い》が2に分類され、《ながれ(B)》は1と3を組み合わせたようなパターン、そして《たそがれ》は5に分類できるだろう。そして絵具の塗り方に着目すると、1から5に進むにつれ、塗りは薄くなって絵具の物質感は減じていき、視覚的要素の純粋性を強めていくことがわかる。

ここで考え合わせたいのが、瑛九がこうした油彩による点描と並行して制作していた、抽象的イメージのフォト・デッサンの存在である。梅津元は、瑛九の関心がさまざまな技法を横断して一貫していることに着目し、フォト・デッサンにおいては、原版となるガラス板やセロファンの上に筆触や絵具の飛沫がオール・オーヴァーに塗られても、それが最終的には光によって印画紙に置き換えられていることに注意を促した(註4)。つまり油彩の点描作品においても、フォト・デッサンと同様に、画家の関心は絵具の物質性の強調ではなく、あくまでイメージそのものに向けられていたと考えられるわけである。

だとすれば、これら瑛九の油彩による点描作品を、パソコンの画面を通して見るという行為は、彼の作品を楽しむ上でむしろ有効なのではないか、と考えてみたくなる。パソコンの画面上では絵具の物質性は限りなくゼロに近づく。そしてイメージは液晶画面の発する光として、私たちの網膜へと届けられることになるからだ。

もちろん、急いで断らなければならないのは、瑛九が生きた時代にはこうした鑑賞方法は想定しうるものではなく、彼にとっての理想的な鑑賞方法は別にあったということである。瑛九を支援していた福井のコレクター木水育男は、次のように証言している。1958年の夏、瑛九から点描の作品《真昼》を贈られた木水は、はじめその作品の良さが理解できなかったというが、「或る晴れた日でした。この絵を庭に出して陽光の下で見たのです。するとどうでしょうか、あれほど気にした黒が銀灰色に輝き、瑛九のあの青も、黄も、赤も、それに呼応して鮮烈に冴え、大きく動くのです。強烈な生命感が、折りしもの陽光にダイナミックに映えかえっているのです。なんという自信、なんという存在、ぼくの内部がうちふるえるのを覚えました」といい、そして翌年「11月、瑛九入院のしらせを受け、浦和の病院へ見舞いました。彼はベッドの上で、『大作が出来ているから、庭に出して張りめぐらしその中で見てほしい。』といいました。ぼくたちはアトリエから大作を庭に出して、彼のいうように見ました。瑛九の宇宙を見たぼくたちの驚きは其の大作をみんなが予約したことでおわかりでしょう」(註5)。

この木水の証言にあるように、瑛九は太陽光の下で自作を見てほしかったようだ。つまり、太陽光が絵の表面に反射して、私たちの目に届くことになるわけで、その際に油絵具ならではの特性が生きてくる。瑛九の最晩年の点描はきわめて薄い「おつゆ描き」だから、下層の絵具も半ば透けて見えるのだ。まばゆい太陽光の下ではなおさら下層の色彩が浮き立つ。そして複数の色点の並置と重層とが、見る者の視覚に作用して、木水の言うように「あれほど気にした黒が銀灰色に輝き、瑛九のあの青も、黄も、赤も、それに呼応して鮮烈に冴え、大きく動く」ことになるのだろう。

こうした効果は、パソコンの画面を通しては味わえない。それからもうひとつ、「庭に出して張りめぐらしその中で見てほしい」というような、絵に囲まれるような鑑賞体験も、パソコンではできないことだ。さきほど問題提起した「瑛九の点描作品の本質」とは、いわば地上のあらゆるものが、太陽の光の下で輝きを帯び、そこに見る者も一体化して生の悦びを実感するような体験をめざすものだとすれば、パソコンの画面で彼の点描作品を見るだけでは、やはり彼の本質を十全には味わえないと言わざるをえない。とはいえ彼も、もともとフォト・デッサンの制作の動機として「私の求めてゐるものは20世紀的な機械の交錯の中に作られるメカニスムの絵画的表現なのです(中略)夜の街頭のめまぐるしく交錯した人工的な光と影は、われわれの機械文化の中に咲いた花なので、われわれの視覚による美もそういつた感覚になければならぬ」(註6)と語っていたのだから、彼がもし今日生きていたら、必ずやこうした新しい視覚体験に関心を持ったにちがいない。私たちは、このウェブ上での展覧会を眺めながら、そんな空想をまじえつつ瑛九が生涯追い求めた光のイメージに思いを巡らせることができる。そして、新型コロナウィルスの脅威が去ったら、あらためて彼の実作を、間近に楽しみたいものだ。

註1 (隆)「厚味ある瑛九の個展」『朝日新聞』1960年2月28日7面

註2 加藤瑞穂「日本におけるアンフォルメルの受容」『草月とその時代 1945―1970』展図録、草月とその時代展実行委員会、1998年10月、pp.88-98

註3 瀬尾典昭「虫のいない午後―瑛九の点描作品」『瑛九 前衛画家の大きな冒険』展図録、渋谷区立松濤美術館、2004年8月、pp.8-9

註4 梅津元「マチエールとジェスチュア」『光の化石 瑛九とフォトグラムの世界』展図録、埼玉県立近代美術館、1997年6月、p.114

註5 木水育男「ぼくは瑛九が好きです。」『現代美術の父 瑛九展』図録、小田急グランドギャラリー、1979年6月、頁付無。

註6 瑛九「私の作品に関して」『瑛九氏フオトデツサン展』目録、大阪・三角堂、宮崎・西村楽器店、1936年6月、頁付無。

60 Years Post-mortem 29th Q Ei Exhibition

To combat the spread of COVID-19, Gallery Toki-no-Wasuremono will hold our very first online exhibition via YouTube. The video was filmed and edited by Shiono Tetsuya of Monthly Free Web Magazine Colla:J. His video pursues a sense of reality as if viewing the works in person at the gallery.

The exhibition can be seen on Toki-no-Wasuremono's YouTube channel, linked below. It will be open to the public from May 8th at 11:00 JST.

Along with the video, please enjoy the accompanying essay authored by Otani Shogo of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

Viewing Q Ei’s Late Pointillist Works Online

Otani Shogo (Chief Curator, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo)

This year, 2020, marks the 60th anniversary of Q Ei’s death. His late pointillist works, “Flow (B)” (1958), “Dance of Red” (1958), and “Tasogare (Dusk)” (1959), were brought together for this commemorative exhibition, which, with the escalating threat of COVID-19, has been moved online. Although it’s a shame to lose the face to face opportunity, perhaps we can take advantage of this opportunity to focus on the experience of viewing works through a computer screen. When considering Q Ei’s work, such an approach surely has some meaning.

Between 1957 and 59, Q Ei expanded his art style from abstract gatherings of small circular shapes to increasingly minute, sensitive pointillism – the fruits of this development were shown at a solo exhibition at Kabutoya Gallery in 1960 (2/23-28). Of this exhibition, Ogawa Masataka wrote the following review:

“Q Ei is holding his first solo exhibition in 6 years. The 9 works from 1958 and beyond range from size 60 (130x97cm) to 200 (259x182cm). In fact, only 2 of the works are smaller than size 100 (162x130cm). Q Ei has been on bedrest since November of last year, but his adamant desire to hold an exhibition as soon as he could, with the help of his friends, made this show possible.

Q Ei is a pioneer of Japan’s avant-garde art, but his work is not well known – perhaps because he never peacocked across the stage of the art world. But when seeing these pieces, I can’t help but feel that the heft of this period of work was a major pillar in the building of this artist who so concretely dedicated himself to his pursuits. Regarding the style, you could say it might belong to a certain art informel trend, but his yellows, blues, greens, oranges… the image borne from these detailed dots of color is a result of precise calculations of compositions of order and color.

It’s precisely the opposite of the impulsive, intuitive work which characterizes art informel. Q Ei calmly manipulates dots of color to create fresh and fantastic spaces full of movement. His work is unique. “Denen (Pastoral)” which inspires the presence of nature, “Flow – Dawn” with its holy light and space. I would call it a splendid effort” (1).

What is interesting about this review is Ogawa’s comparison of Q Ei’s pointillism to art informel. This movement, slowly introduced to Japan from the beginning of the 1950s, gathered major attention after 1956’s Exposition Internationale de l’Art Actuel. Michel Tapie, the art critic considered a major maker of the movement, visited Japan in 1957, triggering a frenzy which was even called the “informel whirlwind”. While the word itself, informel, can mean irregular, undefined, shapeless, a particularly important influence the movement had on Japanese artists, as Kato Mizuho puts forward, was a shift in orientation to a focus on action and material (2). In this regard, Ogawa’s review is correct. Q Ei’s pointillist works are certainly of “undefined shape” in style, but one could easily say of them, “their essence is in fact quite the opposite of the usual impulsive, straightforward style of art informel”. The question now turns to the nature of this “essence”.

Seo Noriaki classified the development of Q Ei’s late pointillist works into the following 5 patterns (3).

1 Works of concentric circles formed by the nesting of small and large circles

2 Works which have “fireworks”, or slightly larger circles which seem to emit sparks, the jagged rings which surround them

3 Works entirely covered by tightly packed pebble-like color circles

4 Works including dynamic movement which seems to pop to the outer edges from a vanishing point painted by lingering brush strokes

5 His final images featuring fine, minute dots

If we were to categorize the works from the current exhibition, “Dance of Red” would fit into category 2, “Flow (B)” into a combination of 1 and 3, and “Tasogare (Dusk)” into 5. If we pay attention to the way the paint was applied, we can see that as the works go from the 1st to 5th category, the application of the paint gradually thins, its materiality reducing, with the purity of the visual elements growing stronger.

What I’d like to take into consideration now are the abstract photo-dessins which he created at the same time as his pointillist oils. Umezu Gen notes that Q Ei’s interest was spread among various mediums but ultimately remained consistent; in terms of photo-dessin, though the brushstrokes and splashes of pigment were painted all over the glass and cellophane that became the base plate, it would ultimately all be transferred by light onto a piece of photo paper (4). In other words, in regards to his pointillist oil paintings, just like his photo-dessin, the artist’s interest was not necessarily in the emphasis of the paint’s materiality, but rather, targeted at the very image itself.

If that is the case, it makes me want to think that viewing Q Ei’s pointillist oil paintings through a computer screen is actually a rather effective way to enjoy them. On a computer screen, the materiality of the paint itself approaches zero. And the image reaches our retinas through rays of light emitted from the LCD screen.

Of course, I must hasten to remind that in Q Ei’s day, this manner of viewing was hardly an option – his own ideal viewing method was something completely different. Kimizu Ikuo, a collector from Fukui and a supporter of Q Ei, made the following statement. In the summer of 1958, when Kimizu first received the pointillist piece “Mahiru (Midday)” from Q Ei, he couldn’t understand its true value. “It was a fine day. I took the painting out to the yard and looked at it in the sunlight. And there, what did I see? – the black I was so concerned about glittered a silver gray, Q Ei’s blues, his yellows, and reds in concert became so vividly brilliant and mobile. It was dynamically reflecting that fierce sense of life from the sunlight of that precise moment. What pride – what presence – I remember how my insides trembled so,” he said. The next year, “in November, I learned of Q Ei’s hospitalization and went to his bedside in Urawa. He lay there in his bed and said, ‘I’ve finished some large works, so I want you to take them out into the yard to see.’ We brought the works from his atelier out into the yard and looked at them like he told us to. -The way we each put in a reservation for one of those large works should be testament to the utter astonishment of those of us who had glimpsed Q Ei’s cosmos” (5).

As relayed in Kimizu’s testimony, it seems that Q Ei wanted his work seen in direct sunlight. That is, as the sunlight reflects off of the surface of the paint and reaches our eyes, the unique quality of the oil paint comes to life. Since Q Ei’s late pointillist works are done in an extremely thin “glaze”, the underlayer of paint appears almost translucent. Under the dazzling sun, the underlayer stands out even more. The juxtaposition and layering of different color dots activates the viewers eye vision so that, as per Kimizu’s recollection, “the black I was so concerned about glittered a silver gray, Q Ei’s blues, his yellows, and reds in concert became so vividly brilliant and mobile”.

This kind of effect cannot be experienced through a computer screen. Neither can “taking them into the yard to see”, the physical experience circling around the works themselves. Regarding the aforementioned problem of “the essence of Q Ei’s pointillism” - if, so to speak, the purpose is for the viewer to encounter the things of this earth bathing under the light of the brilliant sun, and in that act of vision become one with them, and therein experience the joy of life - then it must be said that viewing these works on a computer screen may not in fact provide their complete “essence”. Even so, Q Ei himself wrote regarding the motive for his photo-dessins, “What I’m seeking is a pictorial expression of the mechanisms created in the confusion of the 20th century machine […] The manmade lights and shadows that come together so rapidly among the streetlamps at night are flowers that have bloomed in our machine culture, and so our own vision of beauty must become that sort of sensation as well” (6). Were he alive today, he would surely hold interest in our new forms of seeing. When we encounter online exhibitions, we can ponder that vision as it melds with the image of light that Q Ei sought all his life. And when the threat of COVID-19 finally parts, we can enjoy his works at close range once more.

Reference

1 “An In-Depth Q Ei Solo Exhibition.” Asahi Shimbun, Feb. 28, 1960, p.7

2 Kato Mizuho, “The Reception of Art Informel in Japan”, Sogetsu and Its Era 1945-1970 , Exhibition Catalogue, Sogetsu and Its Era Exhibition Committee, Oct. 1998, pp.88-98

3 Seo Noriaki, “A Bugless Afternoon – Q Ei’s Pointillist Work”, Q Ei The Avant-garde Artists Big Adventure, Exhibition Catalogue, The Shoto Museum of Art, Aug. 2004, pp. 8-9

4 Umezu Gen “Matiere and Gesture”, Fossilization: Imprinted Light Ei-kyu and Photogram Images, Exhibition Catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, Jun. 1997, p.114

5 Kimizu Ikuo, “I Like Q Ei”, Q Ei, Father of Contemporary Art, Exhibition Catalogue, Odakyu Grand Gallery, Jun. 1979

6 Q Ei, “On My Works”, Q Ei Photo-Dessin, Exhibition Catalogue, Sankakudo (Osaka), Nishimura Music Store (Miyazaki), Jun. 1936

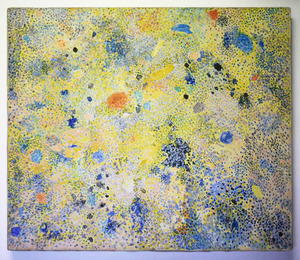

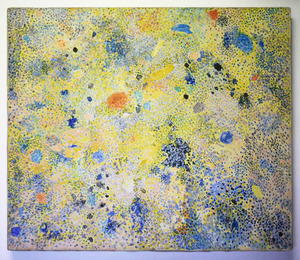

《ながれ(B)》

《ながれ(B)》

1958年

べニア板に油彩

22.0×27.2cm(F3号)

サインあり

※山田光春「瑛九油絵作品写真集」No.344

※レゾネNo.460

《赤の舞い(仮) Dance of Red》

《赤の舞い(仮) Dance of Red》

1958年

べニア板に油彩

22.0×27.2cm(F3号)

サインあり

※山田光春「瑛九油絵作品写真集」No.389

※レゾネNo.444

《たそがれ Tasogare (Dusk)》

《たそがれ Tasogare (Dusk)》

1959年

キャンバスに油彩

45.5×53.0cm(F10号)

サインあり

※「瑛九作品集」(1997年、日本経済新聞社)p.122

※レゾネNo.522

こちらの作品の見積り請求、在庫確認はこちらから

※お問合せには、必ず「件名」「お名前」「連絡先(住所)」を明記してください。

-------------------------------------------------

◎昨日読まれたブログ(archive)/2011年12月22日|磯崎新『栖十二』より第五信チャールズ・レニー・マッキントッシュ[ヒル・ハウス]

-------------------------------------------------

◆ときの忘れものは新型コロナウイルスの感染拡大防止のため、当面の間、臨時休廊とし、スッタフは在宅勤務しています。メールでのお問合せ、ご注文には通常通り対応しています。

◆ときの忘れもののブログは作家、研究者、コレクターの皆さんによるエッセイを掲載し毎日更新を続けています(年中無休)。

皆さんのプロフィールは奇数日の執筆者は4月21日に、偶数日の執筆者は4月24日にご紹介しています。

◆ときの忘れものは版画・写真のエディション作品などをアマゾンに出品しています。

●ときの忘れものは青山から〒113-0021 東京都文京区本駒込5丁目4の1 LAS CASAS に移転しました。

阿部勤設計の新しい空間はWEBマガジン<コラージ2017年12月号18~24頁>に特集されています。JR及び南北線の駒込駅南口から約8分です。

TEL: 03-6902-9530、FAX: 03-6902-9531

E-mail:info@tokinowasuremono.com

営業時間=火曜~土曜の平日11時~19時。*日・月・祝日は休廊。

新型コロナウイルス感染拡大防止のため、画廊始まって以来初めてのWeb展としてYouTubeでの展示を行います。映像制作は『月刊フリーWebマガジン Colla:J(コラージ)』の塩野哲也さんにご担当いただきました。『まるで実際に画廊で作品を見ているような』リアリティーを追求した動画に仕上がりました。

そして、東京国立近代美術館の大谷省吾先生に本展(Web展)についてご執筆いただきましたので、併せてご覧ください。

*Please scroll down for the English text.

ウェブ上で見る瑛九晩年の点描作品

大谷省吾(東京国立近代美術館美術課長)

今年、2020年は瑛九没後60年にあたる。今回の展覧会は、この節目の年にあわせて晩年の点描作品《ながれ(B)》(1958年)、《赤の舞い》(1958年)、《たそがれ》(1959年)が集められたが、新型コロナウィルスの脅威が広がるなか、予防策としてウェブ上での展覧会となってしまった。実物に対面できないのは残念であるけれども、この機会を逆手にとって、瑛九の点描作品をウェブ上で、つまりパソコンの画面を通して見るという体験そのものに意識を向けてみてはどうだろう。彼の作品を考える上で、決して無意味ではないはずだ。

瑛九は1957年から59年にかけて、小さな丸い形の集合のような抽象作品から、次第に細かな点描作品へと作風を展開させ、その成果を1960年の兜屋画廊における個展(2月23日―28日)で発表した。この個展について、小川正隆は次のような批評を書いている。

「瑛九が6年ぶりの個展を開いている。作品は58年以後のもので、60号から200号までの9点。しかも100号以下の作品は2点しかない。彼は昨年11月から病床についているが『できるだけ早く個展を開きたい…』と熱望しており、友人たちの協力でこんど発表にこぎつけたものだ。

瑛九は日本の前衛絵画の先駆者のひとりだが、画壇を舞台に派手な活躍をしなかったせいか、その仕事はあまり知られていない。が、こんどの制作を見ていると、その仕事の厚味とでもいうか、誠実に追求をつづけてきた抽象絵画の、彼なりの一里ヅカを築き上げたという気がする。様式にいえば、ひとつのアンフォルメルの流れに属するだろうが、黄、青、緑、オレンジ……のこまかい色点で描き上げてゆく画面は、的確な秩序――色彩と構成の精巧な計算からなっている。

衝動的、直情的なアンフォルメル一般の仕事とは、まったく本質は逆のものだ。冷静に色点を操作しながら、新鮮な幻想を織り込んだ、かなり動きのある空間を生み出している。ユニークな仕事である。自然のイメージを感じさせる『田園』、神秘的な光と空間を描いた『流れ―れいめい』など。みごとな労作といえよう」(註1)。

この批評で興味深いのは、瑛九の点描作品を、アンフォルメルと比較して論じている点である。1950年代初頭から少しずつ日本に紹介されていたこの動向は、1956年の「世界・今日の美術展」で大きな注目を集め、1957年にこの動向の仕掛人である批評家ミシェル・タピエが来日することにより、「アンフォルメル旋風」とまで呼ばれる大流行が巻き起こることとなった。言葉としては「非定形」「不定形」「無形象」を意味するアンフォルメルだが、日本の作家たちに与えた影響という点では、加藤瑞穂が指摘する通り、行為と物質に目を向けさせたことが重要である(註2)。その点では小川の展評は正しい。たしかに瑛九の点描作品は、様式としては「不定形」であるけれども「衝動的、直情的なアンフォルメル一般の仕事とは、まったく本質は逆のもの」といえるだろう。ではその瑛九の点描作品の「本質」とは何かということが問題になる。

瀬尾典昭は瑛九晩年の点描作品の展開について、次のような5つのパターンに分類している(註3)。

1 大きな丸と小さな丸とが入れ子状態で同心円が形作られる作品

2 花火とよばれる少し大きめの丸の周辺に発光するようなギザギザの輪が取り囲む作品

3 小石のような色丸がびっしり画面を蔽い尽くす作品

4 跡を引くような筆触で消失点から弾けるように外に向かってながれる動きがある作品

5 微細な点描が登場する最後の画面

今回の出品作を当てはめるならば、《赤の舞い》が2に分類され、《ながれ(B)》は1と3を組み合わせたようなパターン、そして《たそがれ》は5に分類できるだろう。そして絵具の塗り方に着目すると、1から5に進むにつれ、塗りは薄くなって絵具の物質感は減じていき、視覚的要素の純粋性を強めていくことがわかる。

ここで考え合わせたいのが、瑛九がこうした油彩による点描と並行して制作していた、抽象的イメージのフォト・デッサンの存在である。梅津元は、瑛九の関心がさまざまな技法を横断して一貫していることに着目し、フォト・デッサンにおいては、原版となるガラス板やセロファンの上に筆触や絵具の飛沫がオール・オーヴァーに塗られても、それが最終的には光によって印画紙に置き換えられていることに注意を促した(註4)。つまり油彩の点描作品においても、フォト・デッサンと同様に、画家の関心は絵具の物質性の強調ではなく、あくまでイメージそのものに向けられていたと考えられるわけである。

だとすれば、これら瑛九の油彩による点描作品を、パソコンの画面を通して見るという行為は、彼の作品を楽しむ上でむしろ有効なのではないか、と考えてみたくなる。パソコンの画面上では絵具の物質性は限りなくゼロに近づく。そしてイメージは液晶画面の発する光として、私たちの網膜へと届けられることになるからだ。

もちろん、急いで断らなければならないのは、瑛九が生きた時代にはこうした鑑賞方法は想定しうるものではなく、彼にとっての理想的な鑑賞方法は別にあったということである。瑛九を支援していた福井のコレクター木水育男は、次のように証言している。1958年の夏、瑛九から点描の作品《真昼》を贈られた木水は、はじめその作品の良さが理解できなかったというが、「或る晴れた日でした。この絵を庭に出して陽光の下で見たのです。するとどうでしょうか、あれほど気にした黒が銀灰色に輝き、瑛九のあの青も、黄も、赤も、それに呼応して鮮烈に冴え、大きく動くのです。強烈な生命感が、折りしもの陽光にダイナミックに映えかえっているのです。なんという自信、なんという存在、ぼくの内部がうちふるえるのを覚えました」といい、そして翌年「11月、瑛九入院のしらせを受け、浦和の病院へ見舞いました。彼はベッドの上で、『大作が出来ているから、庭に出して張りめぐらしその中で見てほしい。』といいました。ぼくたちはアトリエから大作を庭に出して、彼のいうように見ました。瑛九の宇宙を見たぼくたちの驚きは其の大作をみんなが予約したことでおわかりでしょう」(註5)。

この木水の証言にあるように、瑛九は太陽光の下で自作を見てほしかったようだ。つまり、太陽光が絵の表面に反射して、私たちの目に届くことになるわけで、その際に油絵具ならではの特性が生きてくる。瑛九の最晩年の点描はきわめて薄い「おつゆ描き」だから、下層の絵具も半ば透けて見えるのだ。まばゆい太陽光の下ではなおさら下層の色彩が浮き立つ。そして複数の色点の並置と重層とが、見る者の視覚に作用して、木水の言うように「あれほど気にした黒が銀灰色に輝き、瑛九のあの青も、黄も、赤も、それに呼応して鮮烈に冴え、大きく動く」ことになるのだろう。

こうした効果は、パソコンの画面を通しては味わえない。それからもうひとつ、「庭に出して張りめぐらしその中で見てほしい」というような、絵に囲まれるような鑑賞体験も、パソコンではできないことだ。さきほど問題提起した「瑛九の点描作品の本質」とは、いわば地上のあらゆるものが、太陽の光の下で輝きを帯び、そこに見る者も一体化して生の悦びを実感するような体験をめざすものだとすれば、パソコンの画面で彼の点描作品を見るだけでは、やはり彼の本質を十全には味わえないと言わざるをえない。とはいえ彼も、もともとフォト・デッサンの制作の動機として「私の求めてゐるものは20世紀的な機械の交錯の中に作られるメカニスムの絵画的表現なのです(中略)夜の街頭のめまぐるしく交錯した人工的な光と影は、われわれの機械文化の中に咲いた花なので、われわれの視覚による美もそういつた感覚になければならぬ」(註6)と語っていたのだから、彼がもし今日生きていたら、必ずやこうした新しい視覚体験に関心を持ったにちがいない。私たちは、このウェブ上での展覧会を眺めながら、そんな空想をまじえつつ瑛九が生涯追い求めた光のイメージに思いを巡らせることができる。そして、新型コロナウィルスの脅威が去ったら、あらためて彼の実作を、間近に楽しみたいものだ。

註1 (隆)「厚味ある瑛九の個展」『朝日新聞』1960年2月28日7面

註2 加藤瑞穂「日本におけるアンフォルメルの受容」『草月とその時代 1945―1970』展図録、草月とその時代展実行委員会、1998年10月、pp.88-98

註3 瀬尾典昭「虫のいない午後―瑛九の点描作品」『瑛九 前衛画家の大きな冒険』展図録、渋谷区立松濤美術館、2004年8月、pp.8-9

註4 梅津元「マチエールとジェスチュア」『光の化石 瑛九とフォトグラムの世界』展図録、埼玉県立近代美術館、1997年6月、p.114

註5 木水育男「ぼくは瑛九が好きです。」『現代美術の父 瑛九展』図録、小田急グランドギャラリー、1979年6月、頁付無。

註6 瑛九「私の作品に関して」『瑛九氏フオトデツサン展』目録、大阪・三角堂、宮崎・西村楽器店、1936年6月、頁付無。

◆

60 Years Post-mortem 29th Q Ei Exhibition

To combat the spread of COVID-19, Gallery Toki-no-Wasuremono will hold our very first online exhibition via YouTube. The video was filmed and edited by Shiono Tetsuya of Monthly Free Web Magazine Colla:J. His video pursues a sense of reality as if viewing the works in person at the gallery.

The exhibition can be seen on Toki-no-Wasuremono's YouTube channel, linked below. It will be open to the public from May 8th at 11:00 JST.

Along with the video, please enjoy the accompanying essay authored by Otani Shogo of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

Viewing Q Ei’s Late Pointillist Works Online

Otani Shogo (Chief Curator, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo)

This year, 2020, marks the 60th anniversary of Q Ei’s death. His late pointillist works, “Flow (B)” (1958), “Dance of Red” (1958), and “Tasogare (Dusk)” (1959), were brought together for this commemorative exhibition, which, with the escalating threat of COVID-19, has been moved online. Although it’s a shame to lose the face to face opportunity, perhaps we can take advantage of this opportunity to focus on the experience of viewing works through a computer screen. When considering Q Ei’s work, such an approach surely has some meaning.

Between 1957 and 59, Q Ei expanded his art style from abstract gatherings of small circular shapes to increasingly minute, sensitive pointillism – the fruits of this development were shown at a solo exhibition at Kabutoya Gallery in 1960 (2/23-28). Of this exhibition, Ogawa Masataka wrote the following review:

“Q Ei is holding his first solo exhibition in 6 years. The 9 works from 1958 and beyond range from size 60 (130x97cm) to 200 (259x182cm). In fact, only 2 of the works are smaller than size 100 (162x130cm). Q Ei has been on bedrest since November of last year, but his adamant desire to hold an exhibition as soon as he could, with the help of his friends, made this show possible.

Q Ei is a pioneer of Japan’s avant-garde art, but his work is not well known – perhaps because he never peacocked across the stage of the art world. But when seeing these pieces, I can’t help but feel that the heft of this period of work was a major pillar in the building of this artist who so concretely dedicated himself to his pursuits. Regarding the style, you could say it might belong to a certain art informel trend, but his yellows, blues, greens, oranges… the image borne from these detailed dots of color is a result of precise calculations of compositions of order and color.

It’s precisely the opposite of the impulsive, intuitive work which characterizes art informel. Q Ei calmly manipulates dots of color to create fresh and fantastic spaces full of movement. His work is unique. “Denen (Pastoral)” which inspires the presence of nature, “Flow – Dawn” with its holy light and space. I would call it a splendid effort” (1).

What is interesting about this review is Ogawa’s comparison of Q Ei’s pointillism to art informel. This movement, slowly introduced to Japan from the beginning of the 1950s, gathered major attention after 1956’s Exposition Internationale de l’Art Actuel. Michel Tapie, the art critic considered a major maker of the movement, visited Japan in 1957, triggering a frenzy which was even called the “informel whirlwind”. While the word itself, informel, can mean irregular, undefined, shapeless, a particularly important influence the movement had on Japanese artists, as Kato Mizuho puts forward, was a shift in orientation to a focus on action and material (2). In this regard, Ogawa’s review is correct. Q Ei’s pointillist works are certainly of “undefined shape” in style, but one could easily say of them, “their essence is in fact quite the opposite of the usual impulsive, straightforward style of art informel”. The question now turns to the nature of this “essence”.

Seo Noriaki classified the development of Q Ei’s late pointillist works into the following 5 patterns (3).

1 Works of concentric circles formed by the nesting of small and large circles

2 Works which have “fireworks”, or slightly larger circles which seem to emit sparks, the jagged rings which surround them

3 Works entirely covered by tightly packed pebble-like color circles

4 Works including dynamic movement which seems to pop to the outer edges from a vanishing point painted by lingering brush strokes

5 His final images featuring fine, minute dots

If we were to categorize the works from the current exhibition, “Dance of Red” would fit into category 2, “Flow (B)” into a combination of 1 and 3, and “Tasogare (Dusk)” into 5. If we pay attention to the way the paint was applied, we can see that as the works go from the 1st to 5th category, the application of the paint gradually thins, its materiality reducing, with the purity of the visual elements growing stronger.

What I’d like to take into consideration now are the abstract photo-dessins which he created at the same time as his pointillist oils. Umezu Gen notes that Q Ei’s interest was spread among various mediums but ultimately remained consistent; in terms of photo-dessin, though the brushstrokes and splashes of pigment were painted all over the glass and cellophane that became the base plate, it would ultimately all be transferred by light onto a piece of photo paper (4). In other words, in regards to his pointillist oil paintings, just like his photo-dessin, the artist’s interest was not necessarily in the emphasis of the paint’s materiality, but rather, targeted at the very image itself.

If that is the case, it makes me want to think that viewing Q Ei’s pointillist oil paintings through a computer screen is actually a rather effective way to enjoy them. On a computer screen, the materiality of the paint itself approaches zero. And the image reaches our retinas through rays of light emitted from the LCD screen.

Of course, I must hasten to remind that in Q Ei’s day, this manner of viewing was hardly an option – his own ideal viewing method was something completely different. Kimizu Ikuo, a collector from Fukui and a supporter of Q Ei, made the following statement. In the summer of 1958, when Kimizu first received the pointillist piece “Mahiru (Midday)” from Q Ei, he couldn’t understand its true value. “It was a fine day. I took the painting out to the yard and looked at it in the sunlight. And there, what did I see? – the black I was so concerned about glittered a silver gray, Q Ei’s blues, his yellows, and reds in concert became so vividly brilliant and mobile. It was dynamically reflecting that fierce sense of life from the sunlight of that precise moment. What pride – what presence – I remember how my insides trembled so,” he said. The next year, “in November, I learned of Q Ei’s hospitalization and went to his bedside in Urawa. He lay there in his bed and said, ‘I’ve finished some large works, so I want you to take them out into the yard to see.’ We brought the works from his atelier out into the yard and looked at them like he told us to. -The way we each put in a reservation for one of those large works should be testament to the utter astonishment of those of us who had glimpsed Q Ei’s cosmos” (5).

As relayed in Kimizu’s testimony, it seems that Q Ei wanted his work seen in direct sunlight. That is, as the sunlight reflects off of the surface of the paint and reaches our eyes, the unique quality of the oil paint comes to life. Since Q Ei’s late pointillist works are done in an extremely thin “glaze”, the underlayer of paint appears almost translucent. Under the dazzling sun, the underlayer stands out even more. The juxtaposition and layering of different color dots activates the viewers eye vision so that, as per Kimizu’s recollection, “the black I was so concerned about glittered a silver gray, Q Ei’s blues, his yellows, and reds in concert became so vividly brilliant and mobile”.

This kind of effect cannot be experienced through a computer screen. Neither can “taking them into the yard to see”, the physical experience circling around the works themselves. Regarding the aforementioned problem of “the essence of Q Ei’s pointillism” - if, so to speak, the purpose is for the viewer to encounter the things of this earth bathing under the light of the brilliant sun, and in that act of vision become one with them, and therein experience the joy of life - then it must be said that viewing these works on a computer screen may not in fact provide their complete “essence”. Even so, Q Ei himself wrote regarding the motive for his photo-dessins, “What I’m seeking is a pictorial expression of the mechanisms created in the confusion of the 20th century machine […] The manmade lights and shadows that come together so rapidly among the streetlamps at night are flowers that have bloomed in our machine culture, and so our own vision of beauty must become that sort of sensation as well” (6). Were he alive today, he would surely hold interest in our new forms of seeing. When we encounter online exhibitions, we can ponder that vision as it melds with the image of light that Q Ei sought all his life. And when the threat of COVID-19 finally parts, we can enjoy his works at close range once more.

Reference

1 “An In-Depth Q Ei Solo Exhibition.” Asahi Shimbun, Feb. 28, 1960, p.7

2 Kato Mizuho, “The Reception of Art Informel in Japan”, Sogetsu and Its Era 1945-1970 , Exhibition Catalogue, Sogetsu and Its Era Exhibition Committee, Oct. 1998, pp.88-98

3 Seo Noriaki, “A Bugless Afternoon – Q Ei’s Pointillist Work”, Q Ei The Avant-garde Artists Big Adventure, Exhibition Catalogue, The Shoto Museum of Art, Aug. 2004, pp. 8-9

4 Umezu Gen “Matiere and Gesture”, Fossilization: Imprinted Light Ei-kyu and Photogram Images, Exhibition Catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, Jun. 1997, p.114

5 Kimizu Ikuo, “I Like Q Ei”, Q Ei, Father of Contemporary Art, Exhibition Catalogue, Odakyu Grand Gallery, Jun. 1979

6 Q Ei, “On My Works”, Q Ei Photo-Dessin, Exhibition Catalogue, Sankakudo (Osaka), Nishimura Music Store (Miyazaki), Jun. 1936

《ながれ(B)》

《ながれ(B)》1958年

べニア板に油彩

22.0×27.2cm(F3号)

サインあり

※山田光春「瑛九油絵作品写真集」No.344

※レゾネNo.460

《赤の舞い(仮) Dance of Red》

《赤の舞い(仮) Dance of Red》1958年

べニア板に油彩

22.0×27.2cm(F3号)

サインあり

※山田光春「瑛九油絵作品写真集」No.389

※レゾネNo.444

《たそがれ Tasogare (Dusk)》

《たそがれ Tasogare (Dusk)》1959年

キャンバスに油彩

45.5×53.0cm(F10号)

サインあり

※「瑛九作品集」(1997年、日本経済新聞社)p.122

※レゾネNo.522

こちらの作品の見積り請求、在庫確認はこちらから

※お問合せには、必ず「件名」「お名前」「連絡先(住所)」を明記してください。

-------------------------------------------------

◎昨日読まれたブログ(archive)/2011年12月22日|磯崎新『栖十二』より第五信チャールズ・レニー・マッキントッシュ[ヒル・ハウス]

-------------------------------------------------

◆ときの忘れものは新型コロナウイルスの感染拡大防止のため、当面の間、臨時休廊とし、スッタフは在宅勤務しています。メールでのお問合せ、ご注文には通常通り対応しています。

◆ときの忘れもののブログは作家、研究者、コレクターの皆さんによるエッセイを掲載し毎日更新を続けています(年中無休)。

皆さんのプロフィールは奇数日の執筆者は4月21日に、偶数日の執筆者は4月24日にご紹介しています。

◆ときの忘れものは版画・写真のエディション作品などをアマゾンに出品しています。

●ときの忘れものは青山から〒113-0021 東京都文京区本駒込5丁目4の1 LAS CASAS に移転しました。

阿部勤設計の新しい空間はWEBマガジン<コラージ2017年12月号18~24頁>に特集されています。JR及び南北線の駒込駅南口から約8分です。

TEL: 03-6902-9530、FAX: 03-6902-9531

E-mail:info@tokinowasuremono.com

営業時間=火曜~土曜の平日11時~19時。*日・月・祝日は休廊。

コメント